Brain Patterns, Part 2

How Mitochondria and Inflammation Influence the Brain

At some point, many people notice that their brain no longer feels the way it used to.

Sleep becomes harder to regulate. Focus feels less reliable. Thoughts may feel louder, faster, or harder to organize. For others, the shift shows up as brain fog, emotional reactivity, or a sense that stress now hits harder than it once did.

These changes aren’t random — and they aren’t purely psychological.

The brain is an energy-dependent, immune-sensitive organ. When cellular energy production is strained or inflammatory signaling increases, the brain adapts its output accordingly. Over time, those adaptations become noticeable as changes in sleep, cognition, mood, and stress tolerance.

Two common patterns help explain these experiences: the Wired Brain and the Inflamed Brain. They don’t represent failure or malfunction. They describe how the nervous system responds when metabolic and inflammatory pressure has been building beneath the surface.

Pattern 3: The Wired Brain

(Exhausted… but unable to shut down)

This pattern is familiar to many people, even if they wouldn’t use this name for it.

Common experiences include:

Feeling tired all day but alert or restless at night

Difficulty turning off thoughts

A sense of being “on” even when the body wants rest

Productivity driven by pressure rather than ease

Reliance on caffeine, intensity, or urgency to function

From the outside, the Wired Brain can look like high performance. Internally, it often feels unsustainable.

What’s happening neurologically

The Wired Brain reflects chronic sympathetic nervous system activation. Stress signaling becomes the brain’s default operating mode.

Key neurochemical features often include:

Elevated or mistimed cortisol

Increased norepinephrine

Excess glutamate relative to inhibitory signaling

Reduced parasympathetic tone (lower vagal activity)

But this pattern rarely begins with stress alone.

Why mitochondria matter here

Mitochondria do far more than generate ATP. They help regulate how safe — or threatened — the brain perceives the internal environment to be.

When mitochondrial efficiency declines:

Energy availability becomes less predictable

The brain compensates by increasing stress hormones

Cortisol becomes a backup energy signal

Initially, this works. Over time, it creates a system that cannot easily downshift.

This explains why many people with a Wired Brain report:

Trouble sleeping despite exhaustion

Feeling worse with excessive fasting or overtraining

Short-lived relief from relaxation techniques

The issue isn’t a lack of calming strategies.

It’s a nervous system that no longer trusts its energy supply.

Biomarkers commonly associated with a Wired Brain

Labs are often described as “normal,” but patterns tell a different story. Common findings include:

Flattened or inverted cortisol rhythm

Blood glucose variability or elevated fasting glucose

Low-normal ferritin (reduced oxygen delivery = brain stress)

Low RBC magnesium

Elevated BUN/creatinine ratio (stress + dehydration)

Low heart rate variability (HRV)

Individually subtle. Collectively meaningful.

Why common fitness and nutrition advice can worsen this pattern

Well-intended strategies often amplify the problem:

Excessive high-intensity training → further cortisol elevation

Prolonged fasting → increased stress signaling

Aggressive low-carb approaches → reliance on adrenaline

Forcing relaxation → increased nervous system resistance

The Wired Brain doesn’t need more discipline.

It needs metabolic reassurance and consistency.

General actions that support a Wired Brain

Without protocols or personalization, the most helpful principles include:

Stabilizing blood sugar before adding stressors

Supporting hydration and electrolytes

Repleting magnesium

Favoring rhythmic, moderate movement over intensity

Reinforcing circadian cues (light exposure, meal timing, sleep timing)

Reducing late-day cognitive and sensory load

Calm emerges when the system feels resourced — not forced.

Pattern 4: The Inflamed Brain

(Foggy, reactive, less resilient than before)

The Inflamed Brain is quieter than the Wired Brain — but often more disruptive.

Common experiences include:

Brain fog that fluctuates

Heightened emotional reactivity

Reduced tolerance for stress, noise, or stimulation

A sense of heaviness or pressure in the head

Feeling less cognitively flexible than before

This is not a personality shift.

It’s neuroinflammation.

What’s happening inside the brain

Inflammation alters how neurons communicate.

When inflammatory signaling increases:

Microglia (the brain’s immune cells) become activated

Cytokines influence neurotransmitter signaling

Synaptic efficiency decreases

Cognitive processing slows

The result is a brain that feels less clear, less adaptable, and more reactive.

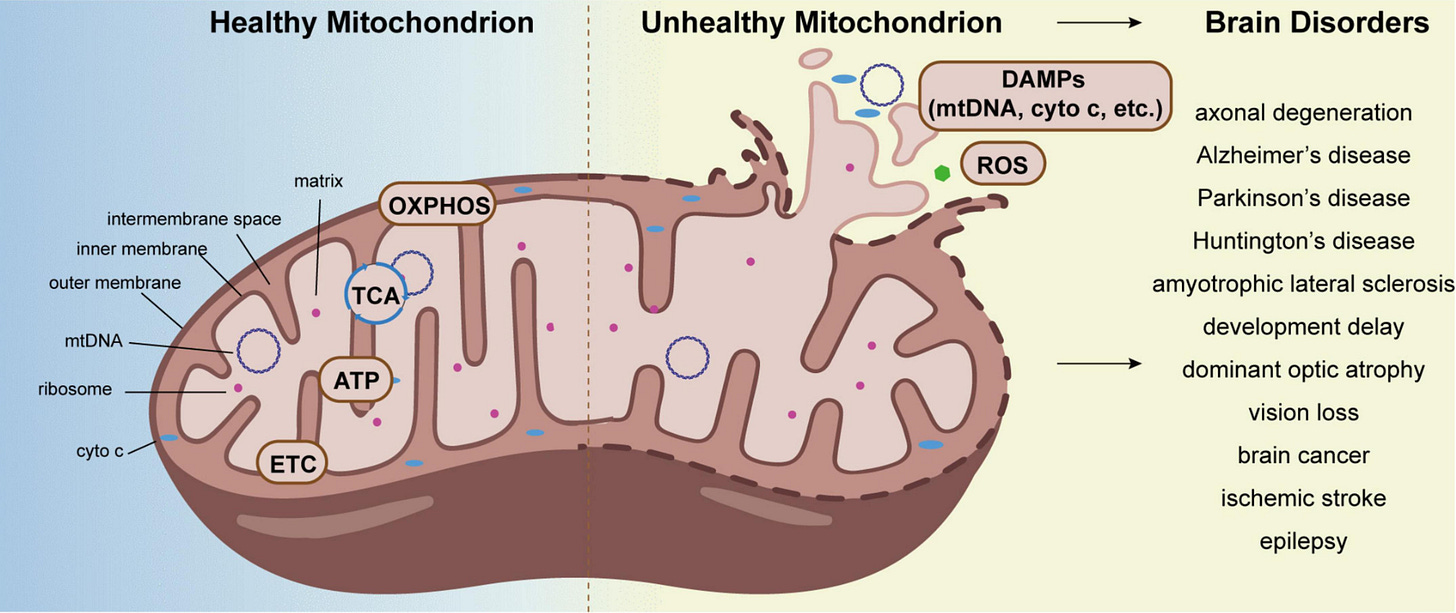

The mitochondria–inflammation feedback loop

Mitochondrial stress and inflammation amplify one another.

When mitochondria are under strain:

Reactive oxygen species increase

Inflammatory signaling rises

Cellular repair capacity decreases

Inflammation then further impairs mitochondrial enzymes, creating a reinforcing loop.

This is why people often say:

“I’m doing anti-inflammatory things, but I still feel inflamed.”

Because inflammation is frequently downstream of energy strain, not separate from it.

Biomarkers commonly associated with an Inflamed Brain

Again, patterns matter more than extremes:

Elevated hs-CRP

High-normal or elevated ferritin

Elevated homocysteine

Increased LDH

Borderline ALT/AST

Markers of gut permeability (when tested)

Low omega-3 index

These markers often live just inside the “acceptable” range — yet align clearly when viewed together.

Why common anti-inflammatory strategies fall short

Inflammation rarely resolves through restriction alone.

Common pitfalls include:

Over-elimination of foods without restoring capacity

Aggressive detoxes that exceed clearance ability

Excessive supplementation adding metabolic burden

Ignoring sleep depth and circadian disruption

Inflammation quiets when the system regains capacity and safety, not just when inputs are removed.

General actions that support an Inflamed Brain

Foundational strategies include:

Reducing inflammatory load without under-fueling

Supporting gut integrity before extreme eliminations

Improving omega-3 intake

Prioritizing sleep depth and regularity

Supporting antioxidant status through whole foods

Lowering cumulative daily stress inputs

Healing requires margin.

Why These Two Patterns Are Often Misidentified

The Wired Brain and the Inflamed Brain are noticeable. They interfere with sleep, mood, focus, and resilience.

As a result, they’re often treated as primary problems — when they’re more accurately adaptive responses to longer-standing metabolic strain.

In many cases, earlier patterns quietly depleted the system first. These patterns simply made the compensation visible.

The brain isn’t failing.

It’s responding.

The Takeaway

If you recognize yourself in either of these patterns, this isn’t a verdict — it’s information.

It tells us:

How your brain has been compensating

Where energy and inflammation intersect

Why willpower-based solutions haven’t worked

When energy production, immune signaling, and nervous system inputs are restored in the right order, the brain doesn’t need to stay wired or inflamed.

Next week, we’ll explore Patterns 5 & 6 — the deeper depletion and disconnection states that often emerge after years of pushing through.

If this article felt uncomfortably specific, that’s not coincidence.

👉 If you want help identifying which pattern is driving your symptoms and where your first domino lives, take the Free Brain Pattern Self-Test.

And if you’d like to be the first to know when enrollment opens for the 2026 NeuroFit Reset, join the waitlist now.

Spots are intentionally limited — because nervous systems don’t heal well in chaos.

Next week, we’ll explore the last 2 patterns- Brain Patterns 5 & 6 — the deeper depletion and disconnection states that often emerge after years of pushing through.

With love & science,

Nikki

References

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(3), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199801153380307

Picard, M., McEwen, B. S., Epel, E. S., & Sandi, C. (2018). An energetic view of stress: Focus on mitochondria. Cell Metabolism, 28(4), 548–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.07.013

Dantzer, R., O’Connor, J. C., Freund, G. G., Johnson, R. W., & Kelley, K. W. (2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(1), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2297

Raison, C. L., Capuron, L., & Miller, A. H. (2013). Cytokines sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 18(12), 1248–1257. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.161

Naviaux, R. K. (2014). Metabolic features of the cell danger response. Mitochondrion, 16, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2013.08.006

Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. (2009). Claude Bernard and the heart–brain connection: Further elaboration of a model of neurovisceral integration. Biological Psychology, 80(2), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.08.004

Frontiers in Neuroscience. (2022). Mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation in neurological disorders. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, Article 1075141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1075141